|

WELCOME TO THE PHOTO GALLERY

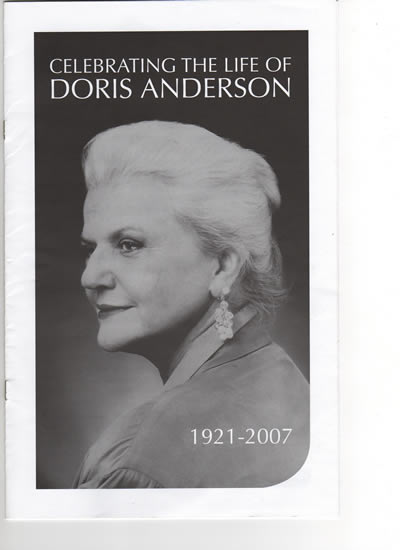

Doris Anderson Memorial Service,

Toronto, Ontario, May 12th, 2007

Photograph and commentary from the May 12th, 2007 Public Memorial Service for one of Canada's feminist leaders, Doris Anderson. The memorial was at Convocation Hall, University of Toronto.

Rebel Daughter, Feminist Revolutionary: Doris Anderson, 1921-2007

Written by Wendy Robbins, PAR-L co-moderator

“What I wanted more than anything was to be able to look after myself and make sure that every other woman in the world could do the same.” So wrote Doris Anderson in her

autobiography, Rebel Daughter. That she largely succeeded in bringing women across Canada closer to this dream was a main theme of the memorial ceremony, “Celebrating the

Life of Doris Anderson,” which took place on Saturday, May 12th, at Convocation Hall, University of Toronto. I was there, coming from Fredericton to pay tribute to a woman

whose feminist editorials in Chatelaine (she edited the magazine from 1957 to 1977) marked my adolescence and influenced the course of my life, like that of so many of us,

baby-boom daughters and mothers coming to our feminist awakenings together.

Prior to the official start of this “public memorial,” a collage of scenes from Doris Anderson’s life, starting in 1920s Medicine Hat, Alberta, scrolled by on two big

screens which flanked the stage. Most were from old black-and-white photos. The images recorded both Doris and the vintage paraphernalia of mid twentieth-century Canadian

womanhood, the era of wide skirts, cinched waists, and flat hats, a stark contrast to the “women’s liberation casual” garb (loose pants, unstructured jackets, and running

shoes) worn by the majority of the older women watching, not always with nostalgia. Later, portions of a documentary film in the CBC’s “Life and Times” series rounded out

Doris Anderson’s life story, highlighting the historic political event for which she is most famous—her protest resignation as president of the Canadian Advisory Council on the

Status of Women (CACSW) in 1981 and her key role in an independent national Ad Hoc Conference on the constitution convened to ensure that women would be comprehensively

included in the new Charter of Rights and Freedoms. All ten memorial service speakers bore witness to Doris Anderson’s professional integrity, personal courage, and “take

charge” leadership, as well as her uncommon kindness to her friends and deep love of her children.

The fact that the celebration was occurring on Mother’s Day weekend was not lost on the hundreds of participants thronging the circular, womb-like hall, many, perhaps even

most of them, gray-haired sixties and seventies activists who joined hands and broke into song at several points. It was a latter-day “love in,” honouring Doris as a

literal mother (one of her three sons regaled the audience with stories of Doris’ living solo, fiercely independent into her eighties, defiant of doctors and of

distances, still driving herself from Toronto to her cottage in PEI) and as a symbolic mother—a mother of second-wave feminism, even a “mother of the nation.” In attendance

was a considerable “who’s who” of Canadian feminist leadership, including two women who had been, like Doris, president of our National Action Committee (NAC) in its glory

days, Lorna Marsden and Judy Rebick.

Journalist and editor Sally Armstrong, who was the MC, began by paying tribute to Doris Anderson as a person who has “changed the way our entire country considers 52% of the

population.” Former Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, who knew Doris since childhood, described Doris as “an electric charge.” Yet, despite her grit and her iconoclasm, Doris

endured sexist experiences where she “just had to take it.” Adrienne Clarkson recalled the time at Chatelaine when Doris, pregnant, was told to go home as the publishers did

not want her working in public in her condition. She also recalled doing book reviews for Chatelaine at Doris’ invitation, bonding further as they went through their

divorces together, and driving around PEI latterly with Doris, ever a caring person, inquiring at one point about the adequacy of the former Governor General’s pension. The

“mothering” side of Doris combined with the strategic feminist leader and astute editor, making her a “whole” woman, stressed Adrienne Clarkson. (Others, however, mentioned how

Doris often felt guilt about her parenting as a divorced single woman, struggling with what we now label work-life balance issues.)

MP and MD Carolyn Bennett, Doris’ physician, recalled the fight that they and many others waged to save Women’s College Hospital, and the support Doris offered when

Carolyn decided to run for political office. (Doris herself had once run under very unfavourable conditions and thus was unsuccessful.) Doris vigorously lobbied for

proportional representation in her later years, wondering impatiently “how anything so sensible could take so long to accomplish.” Carolyn Bennett praised Doris Anderson’s

courage and candour, and called us all to action, proposing a new kind of “D-days.” When she opined, “I think she’d want us to get rid of Steve,” the assembly gasped

(didn’t only “George” get to call our PM “Steve”?) then laughed and ruptured into applause. Such raucous sounds, which seemed to signal the whelping of a renewed women’s

movement, were a fitting dirge for this beloved and feisty feminist champion.

Norma Scarborough of CARAL reminisced about how her mother gave each of her six daughters a subscription of her own to Chatelaine, which, under Doris Anderson,

introduced such “revolutionary” subjects such as female orgasm and women’s sexual satisfaction, the need to repeal the law criminalizing abortion, and calls to

participate in the Royal Commission on the Status of Women—all without losing its mainstream, conventional readers, the “common woman.” Doris Anderson was not writing

for the converted, but rather to make change, an updated Mrs. Beeton, dispensing advice about work, family, and society, along with “no-fail” recipes and affordable fashions.

Julyan Reid and Wendy Lawrence, two people who worked with Doris as president of the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women in the early 1980s, were scheduled as

the next speakers. A last-minute change had Linda Markowsky (formerly MacLeod) substitute for Julyan Reid. She reminded us of the ground-breaking research on the

prevalence and prevention of wife-battering and other violence against women that the CACSW commissioned her to do—research which became a model for the world. Doris

Anderson, she said, exemplified “how to be a strong woman in the world,” a woman who was “sensitively strong” and “pragmatically idealistic.” She paid tribute to Doris for

changing her life profoundly, instilling in her Doris’ own “passion for change.”

Some of the feminist anthems of Doris Anderson’s day movingly punctuated the memorial. Wendy Lawrence introduced “Song of the Soul” by Cris Williamson, with its promise that

“truth will unbind you.” Many of those present still knew all the words by heart. Wendy explained that after Doris’ resignation from the CACSW, she used to get together over

potluck dinners with her former staff, who would sing and dance along with that song. Wendy Lawrence planned the music for the memorial at Doris’ request, and wrote the

“Music Notes” on the back of the program.

Linda Palmer Nye affectionately remembered Doris for her sense of humour. “You really needed it 26 years ago—and we may need it even more today,” she said. In those “heady

times,” Canada could boast a large number of women’s organizations; now even such important groups as NAC and CCLOW have fallen on hard times or folded. She described

the gutsy action of Doris and five of the CACSW staff resigning their positions to protest the decision to cancel a national conference made by the Minister responsible

for the Status of Women, Lloyd Axworthy (yes, a man held that portfolio right into the 1980s). She described the subsequent grassroots mobilization of women from across the

country, and expressed the wish “may it happen again soon.” She said that “Doris made courage look easy,” and observed that “We trusted Doris. When she did something, she

did it for all of us.” Referring to wide-scale political organizing to achieve a goal (e.g., proportional representation), she proposed that we start to “Do it like Doris,

and do it today.” She sang out a song with the ringing chorus “We’re all feminists and we’re damn proud.” Again I felt like a witness to resurrection or rebirth, a

Woodstock-generation “happening” in 2007.

Laurell Ritchie honoured Doris as “quietly seditious” and “extraordinarily principled,” and gave an example of how she bridged differences: Doris defused a divisive debate

about pornography by bringing the opponents together informally and joking that the image in question was “not her style of S & M.” She created coalitions that served NAC

well. Louisa Moya, also of Equal Voice, was the youngest speaker, and she movingly described the impact of her meetings with Doris not long before her death, meetings

which inspired young women like herself to take up the challenges, both of getting a system of proportional representation in place in Canada, and also of running for

political office themselves. She told of how ten young women friends have pledged to run within ten years—in fact, two have already taken steps to do so. The audience

endorsed them all with its enthusiastic applause.

Michele Landsberg said that all women in Canada “owe Doris big time” when it comes to such issues as childcare, Aboriginal women’s rights, and eradicating poverty, racism,

and violence against women. Canadian feminism for a time was, she said, “a decade ahead of American feminism” (an undeveloped allusion perhaps to Doris’ famously turning down

for Chatelaine an extract from Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in the early 1960s). Michele characterized Chatelaine as “a working manual for transforming the

country.” Mothers and daughters read it, “soaking up its feminism, taking this as the norm,” she noted gleefully, her pride obvious for the magazine’s hiding-in-plain-view

subversiveness. There was a time when one in three Canadian women read Chatelaine, “a record unmatched in Canadian journalistic history.” (The magazine featured the writing

of dozens of the country’s best women journalists whom Doris Anderson nurtured, including Adrienne Clarkson, Barbara Frum, June Callwood, and Michele Landsberg

herself.) She, too, cited courage and compassion as Doris Anderson’s defining characteristics; at one point, Doris expressed her concern to channel more work to

Michele when Stephen Lewis, her husband, as new leader of the NDP, finished with his party in third place after an election. She described Doris as “a pioneer with staying

power,” whose energy never flagged. Michele Landsberg suggested that to honour “this woman [who] touched so many lives,” we might dedicate ourselves to completing, as far

as we humanly can, the “unfinished revolution” Doris Anderson cared so passionately about.

Some speakers brought tears, and others laughter. Mitchell Anderson, her son, painted an endearing, humorous portrait of his mother. “She lived like she drove,” he said,

”straight ahead, pretty fast, with not a lot of shoulder checking.” An activist to the core, “If there was something to do, she did it.” This included laying a home-made trip

wire in her cottage to allay concerns about her staying alone there in her eighties. He also noted that one of the greatest thrills of his mother’s life was to be an observer

(or in her case, more like a hands-on participant-observer) in the 1994 election in South Africa that brought Nelson Mandela to power and ended the gross injustice of

apartheid.

With gentle music by the Rose Vaughan Trio, “Stone & Sand & Sea & Sky,” the mood shifted again to emphasize Doris’ love of nature and of PEI (she was for a period Chancellor of

UPEI). Sally Armstrong, closing the ceremony, mentioned the tranquility of her visits with Doris on the island, their long nature walks sometimes punctuated, however, by

political discussion, as when Doris would interject, “Someone’s got to raise a little more hell about proportional representation!”

In conclusion, Mary Lou Fallis, accompanied by Peter Tiefenbach, belted out “Song for Doris,” which she had composed for Doris’ 80th birthday. At that event, Adrienne

Clarkson and John Ralston Saul reportedly picked up their white table napkins and spontaneously waved them as the crowd burst into song. As a parting gesture, white

handkerchiefs were given to everyone at the memorial, and a sea of unstarched white linen, not remotely flags of truce but rather tokens of fond fare-thee-well, waved to

the words “Doris, we sing in chorus,” while the final bigger-than-life portrait of Doris Anderson, mother and crone, faded from the screens. Then Chopin’s “Polonaise in A

Major,” Opus 40, Number 1, Doris Anderson’s music of choice when she was feeling down-hearted and needed to be galvanized into action again, filled the hall as if with

marching orders.

Sisters of all genders, we have some very big shoes to fill; our work is cut out for us.

Donations to a Doris Anderson Fund may be made at the Canadian Women’s Foundation and at Equal Voice.

Yours,

Wendy Robbins

Return to the Photo Gallery

|